Conditions I treat......... High arched feet (Cavus)

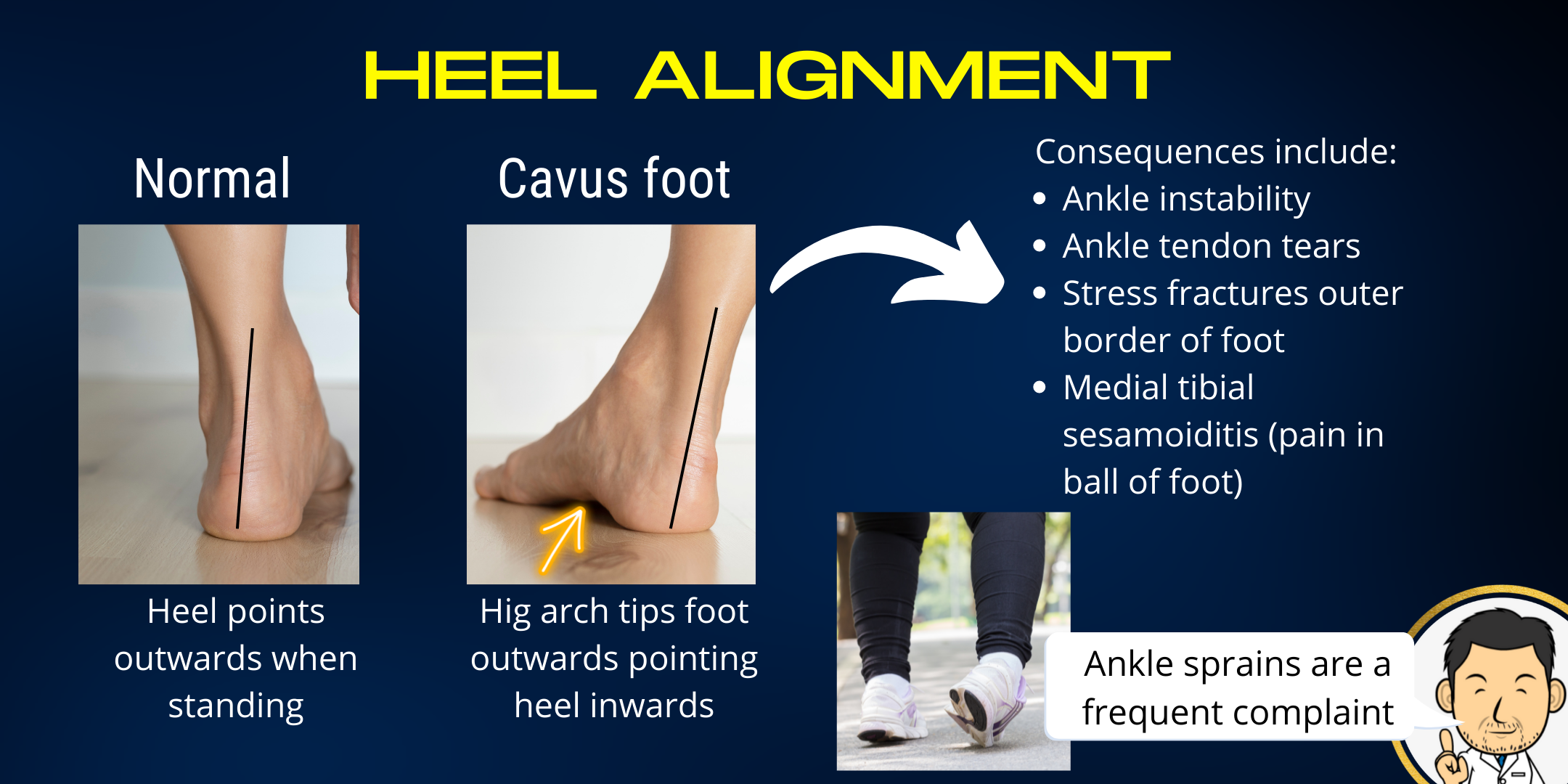

High arched feet are the opposite end of the spectrum to flatfeet. Whereas in flat feet the heel points outwards, in high arched feet the heel may be neutral but often points inwards (heel varus). Patients often end up taking most of their weight through the outside border of the foot which can lead to them going over on their ankle. This can put the foot at risk of repeated ankle sprains resulting in progressive injury to the tendons on the outer aspect of the ankle. The outside of the foot being overloaded can cause stress fractures in these bones. Focussed contact on the ball of the foot (because the arched part is clear of the floor) can cause discomfort here, especially in the small bones within the tendon of the toe (medial sesamoiditis).

Although high arched feet may be seen in several family members, careful assessment is required to make sure that there is no nerve or muscle disorder giving rise to this deformity. This is particularly the case if the high arch is only on one side or the arches have become more pronounced over time. Investigations such as an MRI of the spine and Nerve conduction studies/electromyography can be useful to rule out neurological disorders.

A la carte correction

High arched feet (like all foot deformities) are best approached on an individualised basis. Factors which have a bearing on which steps to undertake in correction include:

- Age of the child - Generally leaving surgical intervention close to skeletal maturity is beneficial to avoid recurrence of deformity with further growth. However, in some neurological causes where there may be progression to severe deformity, early intervention is often mandated to enable the foot to remain braceable for walking.

- How stiff the deformity is - In high arched feet, the heel often adapts to maintain contact with the ground by pointing in but remains flexible. Therefore when you correct the arch, the heel resumes its normal configuration of pointing straight or slightly out. However, in severe deformities the heel can become stiff meaning that it will not adapt once the arch is corrected. In this instance the heel bone needs to be corrected as well as the arch.

- Muscle imbalance and tightness - It is very important to address the driving force of the deformity as usually the high arch arises due to some muscle groups being more powerful than others. Contractures (fixed shortening of muscle-tendon units) often require surgical lengthening. Muscles acting to cause the deformity often need to have their bony attachment points transferred so that their action corrects rather than worsens the deformity.

- Underlying cause - High arched feet due to an underlying neurological disorder are often more challenging to treat due to muscle imbalance arising from weakness, paralysis, high muscle tone or fixed contracture. Often more extensive surgical intervention is required in such feet to correct them.

Serial casting is a strategy I routinely employ in cavus-varus feet to stretch out as much of the deformity as possible. Having less deformity to deal with means small adjustments to individual bones may be all that is required compared to taking out big wedges of bone to correct the alignment of the foot. When it comes to foot surgery, pre-operative serial casting definitely engenders a "less is more" approach. Admittedly, it is time and labour intensive coming back week after week to re-cast. However, it is very rewarding and parents and patients are always impressed by how much correction may be achieved with casting alone.

I prefer an a la carte approach to correction of the deformity depending on the severity and stiffness of the deformity. There are many different elements that can be selectively employed in the surgery:

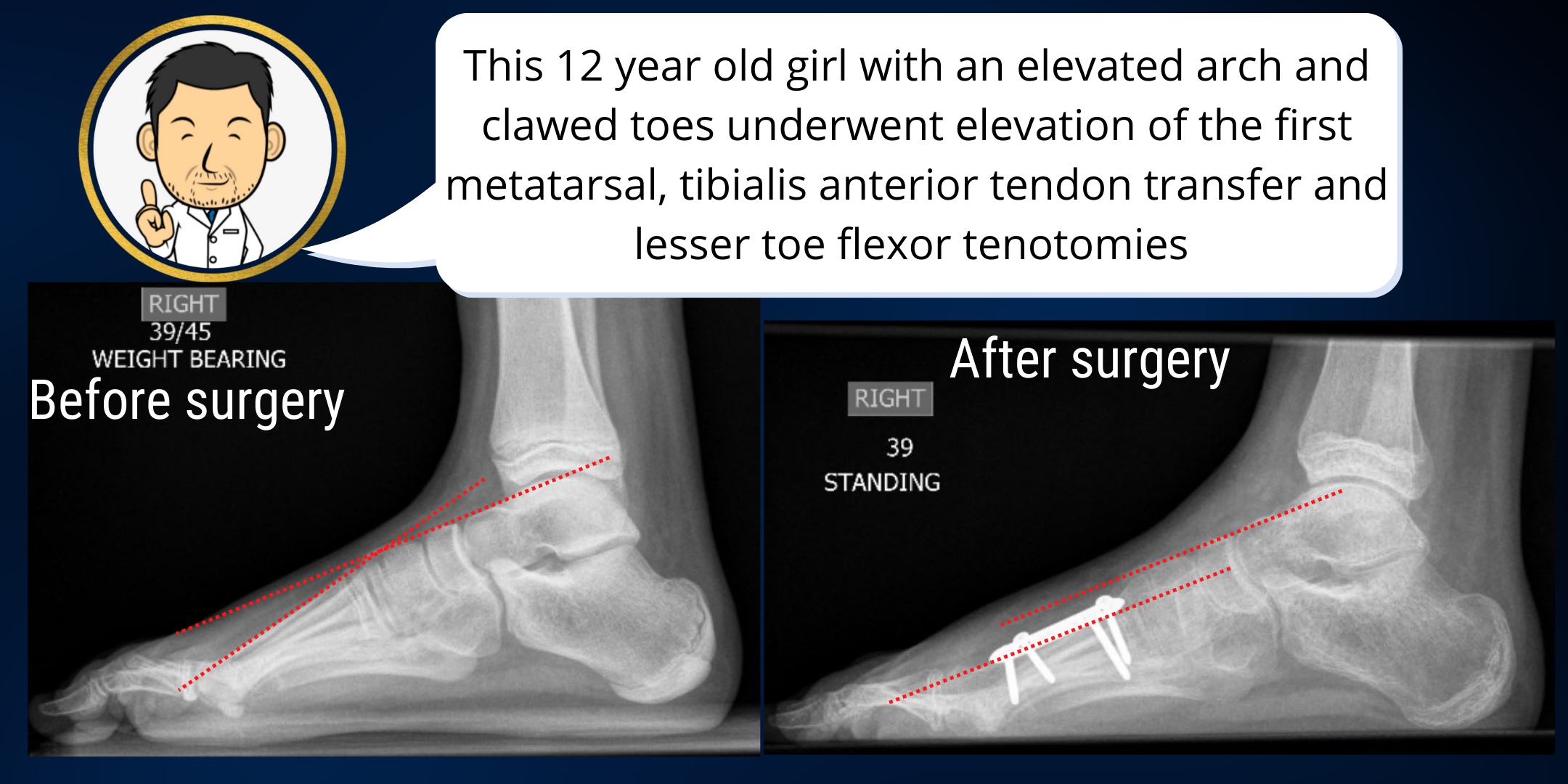

First Metatarsal Osteotomy

This is a correction of the long bone forming the arch of the instep. I usually find that this is the residual deformity that serial casting can't easily correct in an older child. Fortunately it is quite a minimal bony corrective procedure. A small wedge of bone is removed to "flatten" out the bone's inclination. The corrected bone is fixed with a metal plate. If the heel is flexible, "flattening" the instep allows the heel to revert to it's normal alignment of pointing outwards.

Tibialis anterior tendon transfer

This is the second main element of arch correction. The first metatarsal osteotomy corrects the bony element of the deformity. However, the tibalis anterior tendon, a dynamic force pulling up on the arch, needs to be addressed. I usually transfer the attachment point of the tendon to the middle of the top of the foot where rather than pulling up on the instep alone, it pulls the whole foot up.

Jones procedure

I employ this technique when the big toe is cocked up due to the high arch. By detaching the tendon which is pulling the big toe up and moving it upstream where instead it can help pull the whole foot up, we are hoping to "get two birds with one stone." In adult patients, this tendon transfer may be combined with a fusion of the big toe joint to keep it straight. However, in children I often do this as a soft tissue correction by suturing the stump of the tendon to the big toe joint capsule to keep it straight. If the flexor tendon is tight, this can be released through a small opening in the crease of the toe.

Curly toe correction

If the little toes (numbered 2 to 5) are also curled up then I correct these by cutting the tendon through a small nick in the skin crease under the toe. I've found the toees come out straight with no impact on function (perhaps because we walk in shoes much of the time and we don't need a vice like grip in our little toes to grip wet rocks when we have to escape a sabre tooth tiger across a fjord).

Tibialis posterior tendon transfer/recession

The tibialis posterior tendon is very important to foot function - it helps the foot arch into a rigid lever when we go on tiptoes to propel us forward during walking. Tibialis posterior transfer to the top of the foot is well documented (and undertaken in many big centres) for high arched feet driven by neurological disorders. However, it's not a procedure I routinely undertake due to my fears of de-functioning this crucial muscle. When it is over-active or tight, my preference is to lengthen the muscle- tendon unit to "de-power" it rather than transfer it completely. There are many instances in foot and ankle surgery where it is far better to err on the side of "under-correction" rather than over-correction" and this is definitely one of them.

Calcaneal osteotomy/heel transfer

When the arch is corrected but the heel is rigid and doesn't revert to it's normal alignment, osteotomy through the heel bone to correct it's alignment is usually necessary to restore the foot's anatomy. The heel bone is fixed with one or two screws.

Calf muscle/tendo achilles lengthening

When the calf muscles are tight, lengthening may be required. This can be done in many different ways. The most important technical point is to ensure that you don't "over-lengthen" the tendon and make it functionally incompetent. If the tendon is over-lengthened, especially in children with cerebral palsy, it will push them into a "crouch gait" walking pattern.

To avoid over lengthening, I don't opt for open "z-lengthening"where the tendon is divided in two before re-attaching in a lengthened position. I usually lengthen the muscle-tendon complex by dividing elements rather than completely transecting the tendon. Intramuscular lengthening, dividing the fascia over the tight muscle and incomplete sectioning of the tendon are all techniques I use to minimise the risk of "over-lengthening."